Every day, I turn the doorknob, and the moment I step through the door, it’s like all the tension in my brain just melts away. It’s like a balloon slowly deflating—with each step into my home, I feel lighter and more relaxed.

So I collapse onto the couch, grab my phone, and start mindlessly scrolling through TikTok, Reddit, and X.

Before I know it, I realize it’s way past dinner time. I’ve been scrolling for a solid hour and a half.

Then I remember all the things I still need to do: cook dinner, order takeout, or maybe even hit the basketball court with friends later. That wasted hour and a half suddenly feels like a cardinal sin. TikTok really is a time killer—pure evil.

Wait. Hold up. Is TikTok really the villain here?

Daily Struggle with Distractions

Do you have those days each month when you set these grand plans for self-improvement, only to end up like me—slouched on the couch, feeling deflated, thinking, “Man, being glued to my phone just feels so good!”? And then, after that dopamine hit, you start beating yourself up: “This app is destroying me! All these endless-scroll apps are pure evil!” The addiction only gets worse in the following days, until you finally tell yourself, “I can’t keep living like this—I need to get my act together,” and you start planning again.

You roll out your carefully crafted plans, but after a few days, they become impossible to stick to. Then one day, you come home, unconsciously sink into the couch, pick up your phone, and tell yourself, “It’s fine to indulge just a little bit…” And the cycle starts all over again.

Let me ask you again: Is TikTok really the villain here?

About six months ago, I had a realization: the real villain isn’t TikTok, and it’s not endless-scroll apps either.

If you look closely at what I described earlier, you’ll notice that every time my plans fall apart and I lose motivation, it never starts with picking up the phone.

It starts with the simple act of lying down on the couch.

Only when I lie on the couch do I lose motivation and start endlessly scrolling on my phone.

Notice that I’m actually describing three separate actions: Lying on the couch → Picking up my phone → Scrolling endlessly.

This chain of actions pulls you in like a massive whirlpool in the Pacific Ocean, dragging you deeper and deeper.

But here’s what I want you to understand: the difficulty of saving yourself is vastly different between “being at the edge of the whirlpool” and “almost being sucked into the center.”

In other words, “realizing you shouldn’t use your phone the moment you lie on the couch and immediately getting up to do what you need to do” is hundreds of times easier than “realizing you’ve been scrolling TikTok for way too long and trying to snap out of it to be productive.”

And “not sitting on the couch when you get home” is hundreds of times easier than “lying on the couch, realizing you shouldn’t use your phone, and forcing yourself to get up.”

This is what I mean by finding the root cause.

Building self-discipline isn’t about suddenly snapping out of an unproductive binge, dropping everything, and becoming productive. Human nature makes it incredibly easy to get lost in endless content and distractions. You can’t expect yourself to party all night and then immediately sit down to write a serious paper or report—unless there’s a looming deadline. That goes against human nature.

Building self-discipline is about identifying the root of unproductive behavior and avoiding stepping into that whirlpool before it pulls you in.

This guide focuses on two key parts: “finding the root of unproductive behavior” and “avoiding the whirlpool.”

Find the Root of Your Unproductive Behavior

As I mentioned earlier: Only when I lie on the couch do I lose motivation and start scrolling on my phone endlessly.

This behavioral chain makes perfect sense: the couch provides a comfortable environment, lying down makes it nearly impossible to read or exercise, and the phone becomes the couch’s natural companion.

But for you, the key isn’t whether the behavioral chain makes logical sense—it’s whether you can trace back to the initial trigger.

The couch is just my example. For you, the initial trigger might be a specific thought or the completion of a task. But I don’t recommend trying to find the initial trigger through complicated methods like recording yourself or keeping detailed journals—at least not at first.

Instead, mentally trace back your behavioral chain and see if you can identify the initial event and whether it can be changed.

For example, if you’re a student trying to overcome video game addiction, your behavioral chain might look like this: Get home → Enter bedroom → Turn on computer → Play games.

Here, the initial event is getting home. Can you avoid coming home? Technically, yes, but the cost is way too high, nowhere is as comfortable as your own room, and you’d have to deal with your parents’ endless questions and concerns. So getting home can’t be changed.

Next, let’s evaluate the next behavior: entering the bedroom. Can you avoid entering your bedroom? Yes, but if you don’t go to your bedroom, you’d have to hang out in the yard or living room. What can you do there? Maybe you can take over dog-walking duties from your mom.

But this still isn’t the crucial point. Because if you want to avoid game addiction, you’re only delaying entering your bedroom—eventually, you’ll have to go in. So avoiding the bedroom helps, but not significantly.

Next: turning on the computer. Can you avoid turning on the computer? In my experience, if I’m sitting at my computer, I will turn it on and play games. In other words, turning on the computer → playing games is a tightly bound sequence.

The real problem is here. If I’m at the computer, I will turn it on. But what if I’m not at the computer?

This realization updates the behavioral chain: Get home → Enter bedroom → Sit at computer → Turn on computer → Play games.

Now, you’re in your bedroom but not at the computer. Where else can you sit? If you only have one chair and one desk, you can’t sit anywhere else except at the computer or on the bed. But what if you had another desk?

At this second desk, you can’t turn on the computer—you can only use it for reading or studying. Sure, you could still use your phone, but I have a solution for that later. For now, the theme remains: finding the root of unproductive behavior.

Imagine your room has a second desk. To sit there, you must move the chair from your computer desk. Once you’re seated, even if you feel the urge to play games, you’ll face a small obstacle: moving the chair back is a hassle. So you end up spending your time productively at the second desk.

Have you found the root cause? In this case, I’d say yes—the behavior of “sitting at the computer” is the root trigger for game addiction.

I’m not saying you need to find some deep psychological reason for your addiction—that’s for researchers to study. Here, we’re looking for the factor that pulls you into the whirlpool. Only by identifying it can you plan to avoid it and build self-discipline.

Now, try identifying your own behavioral chain below. Go ahead and write it down—this is just for demonstration purposes, and your data won’t be collected. You can also write it down on paper.

Avoid the Whirlpool

For me, if the only issue were TikTok or game addiction, it wouldn’t be a huge problem. As I said earlier, I just need to avoid sitting or lying in that particular spot. But life’s challenges don’t end there.

Improving self-discipline isn’t just about the moment you get home—it requires sustained effort and long-term planning. In other words, the behavioral chain I described earlier isn’t enough to support a complete self-discipline improvement plan.

When I play games, I get addicted—and the consequences aren’t just neglecting other aspects of life. It also makes it way too easy to stay up late. Once you stay up late, your mental state the next day is absolutely terrible. After forcing yourself to wake up early and struggle through the day, you come home completely drained.

You won’t even consider using self-discipline to improve yourself—you’re too exhausted and just want to sleep. But if you sleep now, your sleep schedule gets completely messed up, so you try to find something to keep you awake. Studying? You’ll fall asleep in ten seconds. Exercising? You’re afraid you might actually collapse.

It seems like the only option is to play games. A round of Dota 2 can keep me alert for fifty minutes. And as expected, a few rounds later, it’s already 1 a.m. The cycle repeats.

Staying up late affects your entire next day and completely disrupts your self-discipline plan.

Another example: After eating, I’d rather sit and scroll on my phone instead of washing the dishes right away. Before I know it, a ton of time has passed.

This is my experience. I’ve written down these behavioral chains and connected them into a full-day event log. You can do the same:

When you write them down, you’ll see that these behavioral chains form a stable structure that maintains your current state. I prefer organizing them into a table:

| Trigger Point | Original Behavior Pattern | Control Strategy |

| After Getting Home | Sit at computer → Steam auto-launches | Don’t sit at computer; disable auto-start |

| Cooking Takes Too Long | Only one stove; prep is slow | Prepare meals on weekends, do food prep in advance |

| Bedtime Phone Use | TikTok → Reddit → late night | Limit phone use; leave it on couch after midnight |

| … | … | … |

Note: Creating a table like this isn’t about rigidly following it—it’s about first finding a solution. How you implement the solution is the next step.

Based on your behavioral chain, I’ve generated the table below. The rightmost column is for you to fill in:

| Trigger Point | Original Behavior Pattern | Control Strategy |

|---|---|---|

Now, we have a comprehensive set of behavioral chains covering all aspects of your life that you want to improve. You already know the solutions for these behavioral chains, but integrating or managing them directly is incredibly difficult.

Why? Because your mind and body are already accustomed to the old behavioral chains. Your current behavioral chains are like deep roots—pulling out the entire tree is extremely hard.

Instead, if your task is transplanting or grafting—once part of it succeeds, you can cut away or remove parts of the old tree—this approach is much easier than uprooting the whole thing.

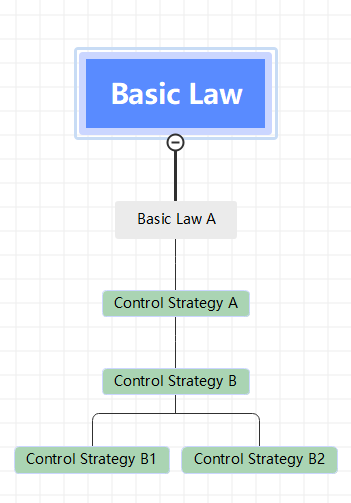

What we need to do now is establish a backbone for your life—a positive core behavioral chain that runs through all your actions. Since “behavioral chain” here refers to “behaviors to correct,” I’ll call this positive core the “Basic Law.”

Creating a Positive Core (Basic Law)

Time-Based Basic Law

I recommend starting with time. Time is the easiest constraint. Compared to “wash the dishes immediately after eating,” an alarm suddenly going off at a set time is much more effective.

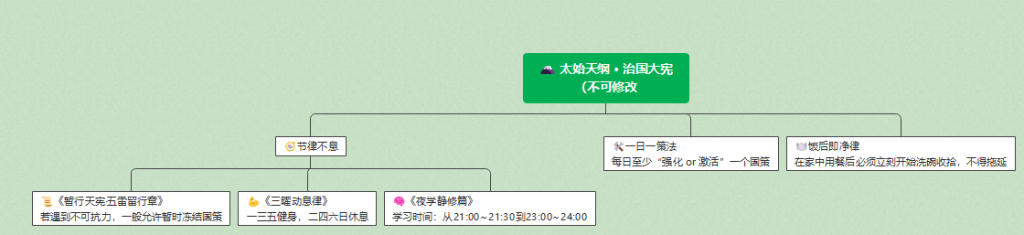

My Basic Law is shown below. Two of its items are time-related, translated as:

- The Sutra of Three-Day Vital Motion: Train on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Rest on Tuesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays, and Sundays, letting the body gather its qi.

- The Chapter of Nightly Cultivation: Learning hours—from 9 PM until 11 PM, or from 9:30 PM until midnight.

Yes, to make it more fun, my Basic Law is written in a cultivation novel style. For example, the general policy for “encountering irresistible circumstances—freeze the Basic Law” is written as “Heaven’s Temporary Edict · Scroll of the Five Thunders in Motion.” You can customize and modify yours however you like.

Integrating Control Strategies

How does the Basic Law relate to the behavioral chains? The Basic Law is the foundation for the control strategies in your behavioral chains. Once you set a Basic Law, you need to integrate your control strategies around it.

The method is simple: use a tree structure (this is mandatory). Place your Control Strategy A under Basic Law A. If there are highly related sub-strategies, place them under Control Strategy A.

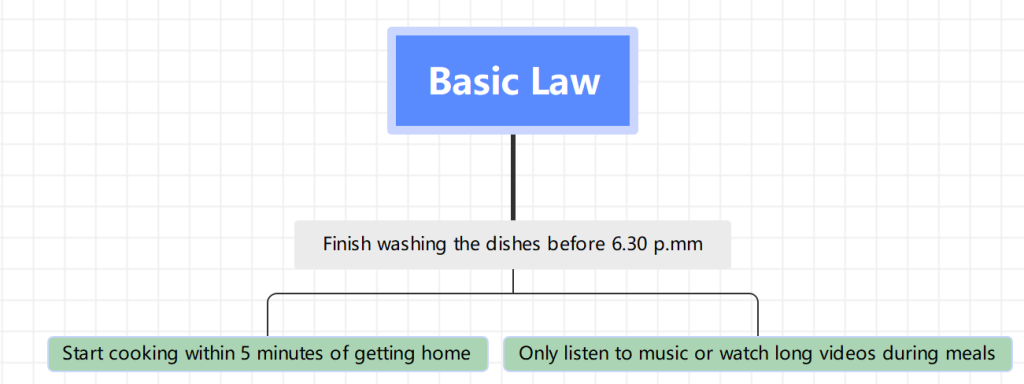

For example, if I want to reduce the time spent dealing with hunger, and my Basic Law states: “Must finish washing dishes by 6:30 PM,” then my cooking and eating-related behavioral chains can fall under this Basic Law.

For instance, these two behavioral chains:

| Trigger Point | Original Behavior Pattern | Control Strategy |

| After Getting Home | Lie on couch → Scroll Reddit | Start cooking within 5 minutes of getting home |

| Meal Time | Scroll feeds → pause chewing | Only listen to music or watch long videos during meals (to eat faster) |

We then add the control strategies under this Basic Law:

This way, you have a complete control chain—comprising the Basic Law and control strategies—to avoid prolonged meal times. When you get home each day, just follow your customized guidelines to safely and efficiently get through this period.

Another advantage of this control chain approach is that you only see improvement measures, not the behaviors and reasons from your original behavioral chains. This keeps you away from triggering terms like “Reddit.”

If you include the reason “Lie on couch → Scroll Reddit” in the control chain, you’ll still be reminded of “Reddit,” increasing the chance you’ll actually open the app. So I recommend only adding improvement measures to the control chain.

Rules for the Control Chain

Now, let’s move to the second step of building the control chain: Where’s the constraint?

Yes, if you just create a control chain by yourself, it’s no different from making a schedule to follow. I believe most people struggle to stick to schedules, let alone overcome unproductive states.

I want to tell you: That’s totally okay.

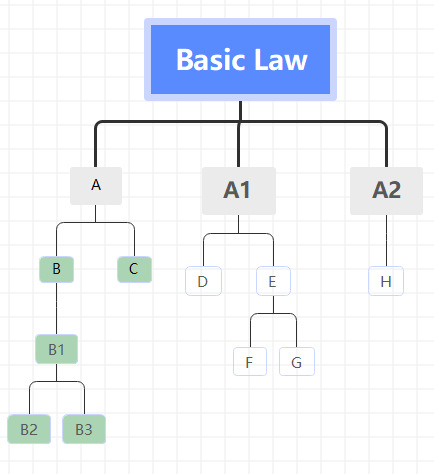

Earlier, I said you must design it in a tree structure. The tree structure is the key to creating constraint.

Now, I’ll give you two rules for using the control chain:

I. You can only add one new control strategy per day, and it must be practiced. II. If you can’t follow one of the control strategies, delete it immediately.

You must understand: these two rules are not gentle—they are extremely aggressive.

Suppose today is the seventh day of following your control chain. By now, you should have:

- 2-3 Basic Laws

- 4-5 control strategies from day one

- 3-4 new control strategies added one by one over the days

On the seventh day, you find you can’t complete Strategy B. According to Rule II, you must delete Strategy B.

You might ask: If B is deleted, what happens to B1, B2, and B3?

Answer: Delete them all. Because B1, B2, and B3 all belong to B.

This means the entire branch of control strategies under B—which took you three days to build—is now completely wiped out. The cost is significant.

This is just after seven days. If this control chain has been running for two months, and the branch under B has grown extensively, deleting B would be a massive loss. Imagine how you’d feel if a close online friend you’ve known for seven years suddenly disappeared.

But precisely because the cost is so high, you’ll work much harder to protect Strategy B, the root control strategy. And as B is protected over time, it becomes more reliable and gradually becomes the foundation of your new habit. Eventually, B becomes your new habit.

This is the beauty of the tree structure combined with these two rules.

Now, let me explain the principles behind the two rules:

I. You can only add one new control strategy per day, and it must be practiced. II. If you can’t follow one of the control strategies, delete it immediately.

These rules greatly increase constraint, making you much more cautious when adding new control strategies. They add time and opportunity costs, making you more rational and careful when creating new strategies, reducing the probability of adding ones you can’t sustain.

Now, based on the behavioral chains you’ve written, you can create a tree-diagram control chain. Start with one Basic Law and design an initial version of your control chain based on your behavioral chains.

| Trigger Point | Original Behavior Pattern | Control Strategy |

|---|---|---|

Tools and Tips

As for tools, I recommend mind-mapping software on your tablet or computer. If you prefer analog methods, buy a small whiteboard and hang it somewhere convenient for easy editing. But as your control chain grows, you'll likely need digital tools eventually.

If you have other ideas, feel free to share them.

From here, most of our problem is solved.

One small note—this is my personal experience, and it may not apply to everyone: For me, it's best to start with as few Basic Laws as possible. If I start with too many, I'm likely to overlook some because my attention is focused on the first few. Of course, if you can handle five Basic Laws with full attention, that's perfectly fine.

Actually, I suspect most people coming to this page to solve self-discipline issues ultimately want to focus on learning. Whether it's academics, useful courses, or instruments—it's all about investing in your future, which is why you're motivated to improve self-discipline.

Next Steps: Focusing on Learning

However, the method I've given you—the control chain tree-diagram method—only helps you manage your daily timeline, not your focus during non-routine activities like learning.

In other words, for productivity activities—like if your control chain sets study time from 8:30 PM—this method makes it easy to sit down and start studying at 8:30. But it can't ensure you stay focused from 8:30 to 10:00 without getting distracted.

What? You can maintain focus? Then congratulations! But generally, people seeking help with self-discipline struggle with focus, whether in daily schedules or study concentration.

But—that's totally fine. We can create a "Study Basic Law" within the control chain and add a dream-like focus control method to fully manage your study concentration.

I can help solve this, but I prefer to cover it in the next chapter.

Stay tuned for the next chapter: How to Focus on Learning!

Thanks for reading!